Table of Contents

Most Big Data developers and Data Engineers start learning Spark by writing SparkSQL codes to perform ETL on DataFrame (I know I did). I also wrote a post about SparkSQL Programming. However, we quickly learn that there’s more knowlege required to go from processing a few GBs of data to dealing with TBs and PBs of data, which is a challenge for big enterprises. Learning to write correct Spark codes is only a small part of the battle, you will need to understand the Spark Architecture and Spark working internals to correct tune Spark to handle true big data, and it’s the focus of this post.

Spark Architecture

First, let this sink in: Spark is an in-memory, parallel processing engine that is very scalable. The more data you have, the more powerful Spark can become that sets it apart from other processing engines. Spark is faster than Map Reduce paradigm because it processes data in memory, which means that it can reduce the disk IO that normally slows down Map Reduce jobs. Spark is fast because of the ability to process data in parallel.

Parallelism is key enabler of Spark efficiency. The Spark Architecture is designed so that you can add new computers to process growing amount of big data in parallel.

Spark Cluster Components

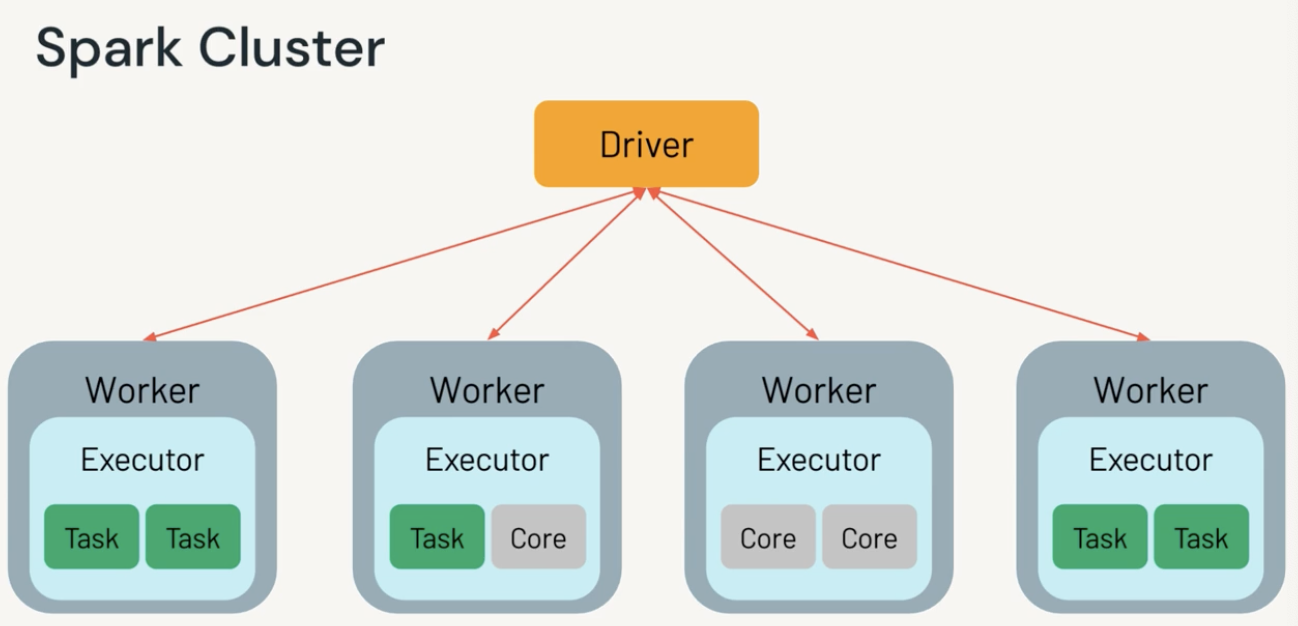

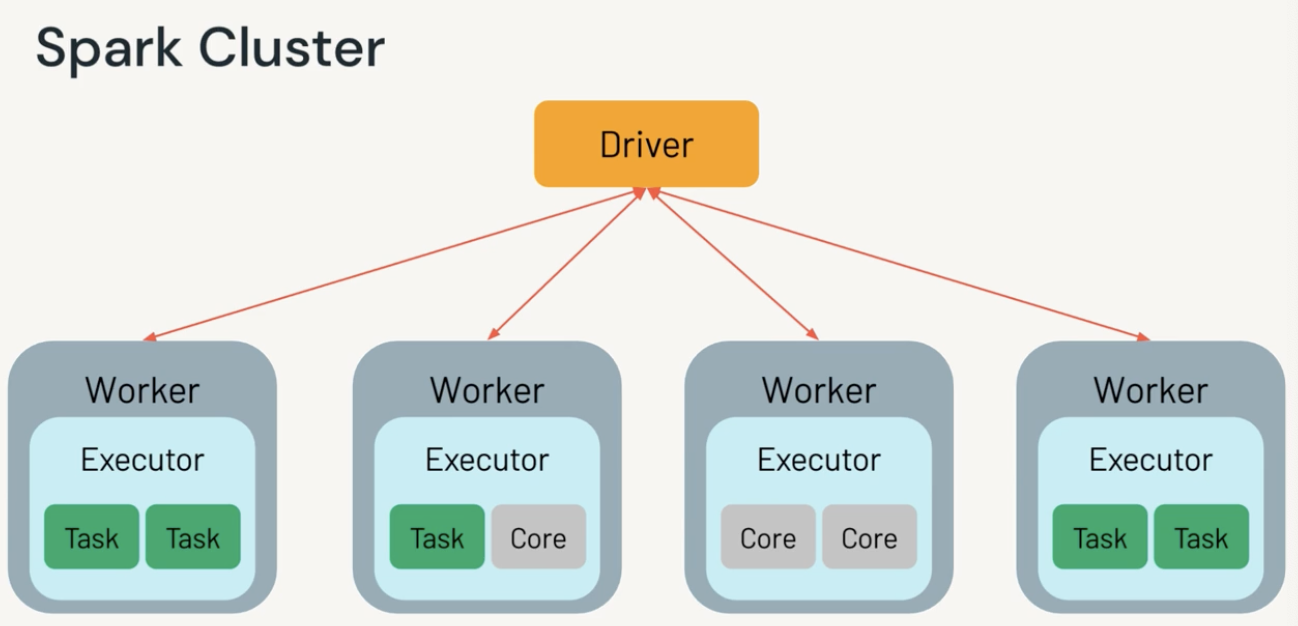

A Spark cluster has, a driver and mutiple workers (think computers).

- Spark driver (JVMs) is responsible for instantiate Spark Session, turn Spark operations into DAGs, schedule and distribute tasks to the workers.

- Each worker has multiple cores (think threads) that can run multiple tasks. Each task is a single unit of work, each task maps to a single core and works on a single partition of data at a given time (1 task, 1 partition, 1 slot, 1 core)

- Besides, we also have a cluster manager, and Spark Session that runs Spark applications.

Spark Session

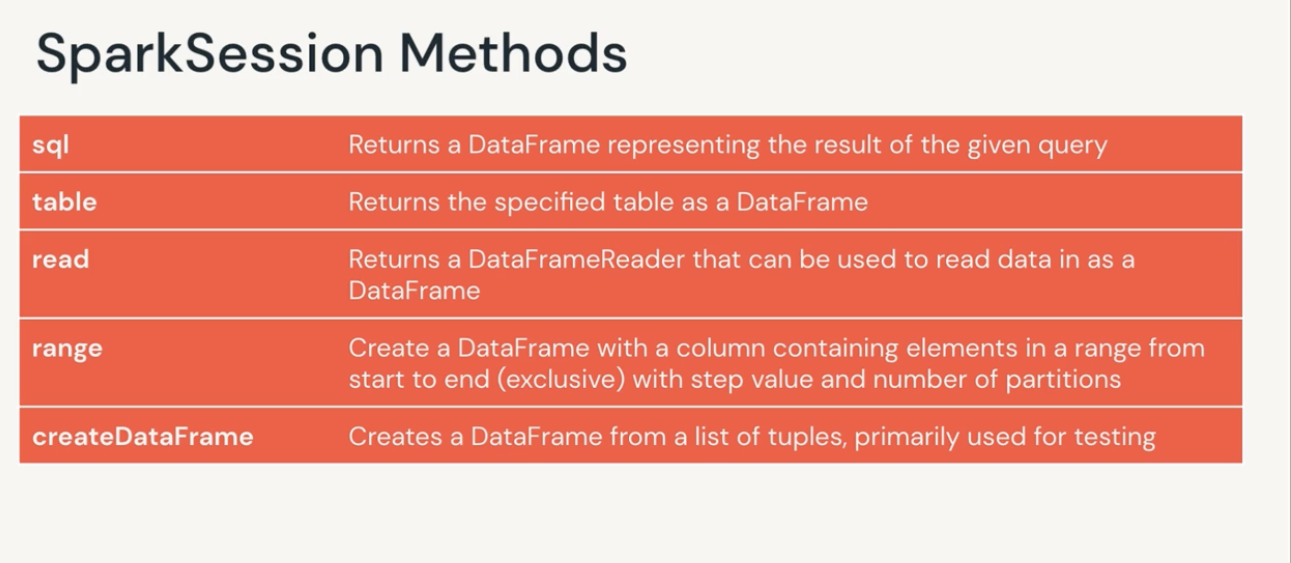

SparkSession is the single point of entry to all DataFrame API functionality. SparkSession is available since Spark 2.0, before that Spark Context was used with a limitation of only one Spark Context per JVM. SparkSession can unify numerous Spark Contexts.

SparkSession automatically created in a Databricks notebook as the variable spark.

# In below code, the `spark` variable specifies a sparkSession

# spark.table reads a table to a dataframe

df = spark.table('<table>')

.select('a', 'b')

.where('a>1')

.orderBy('b')

# spark.read reads files to a dataframe

df = spark.read.parquet('path/to/parquet')

# spark.sql execute sql queries on a table and save the result set to df

df = spark.sql('select * from <table>')

Spark APIs

Spark ecosystems have 4 APIs: SparkSQL, Spark Structured Streaming, SparkML, and GraphX (I haven’t used this before, not sure if it’s deprecated or not). Most of Spark developers started with SparkSQL APIs with ingestion and transformations on Spark DataFrame. However, Spark Structured Streaming and SparkML are pretty popular too, which we can discuss later in later posts.

Computation in Spark

Earlier I mentioned that Driver is responsible to turn operations into jobs or DAGs. DAGs are Directed Acyclic Graphs (fancy word for graphs that have direction with no cycle). In a spark execution plan, each job is a DAG, each node within a DAG can have one or multiple stages, each stage can have multiple tasks (clear?)

Spark parallelizes at 2 levels:

- splitting work among workers, executors (or workers) will run the spark code on the data partitions it has

- each executors have a number of slots/cores, each slot can execute a task on a data partition.

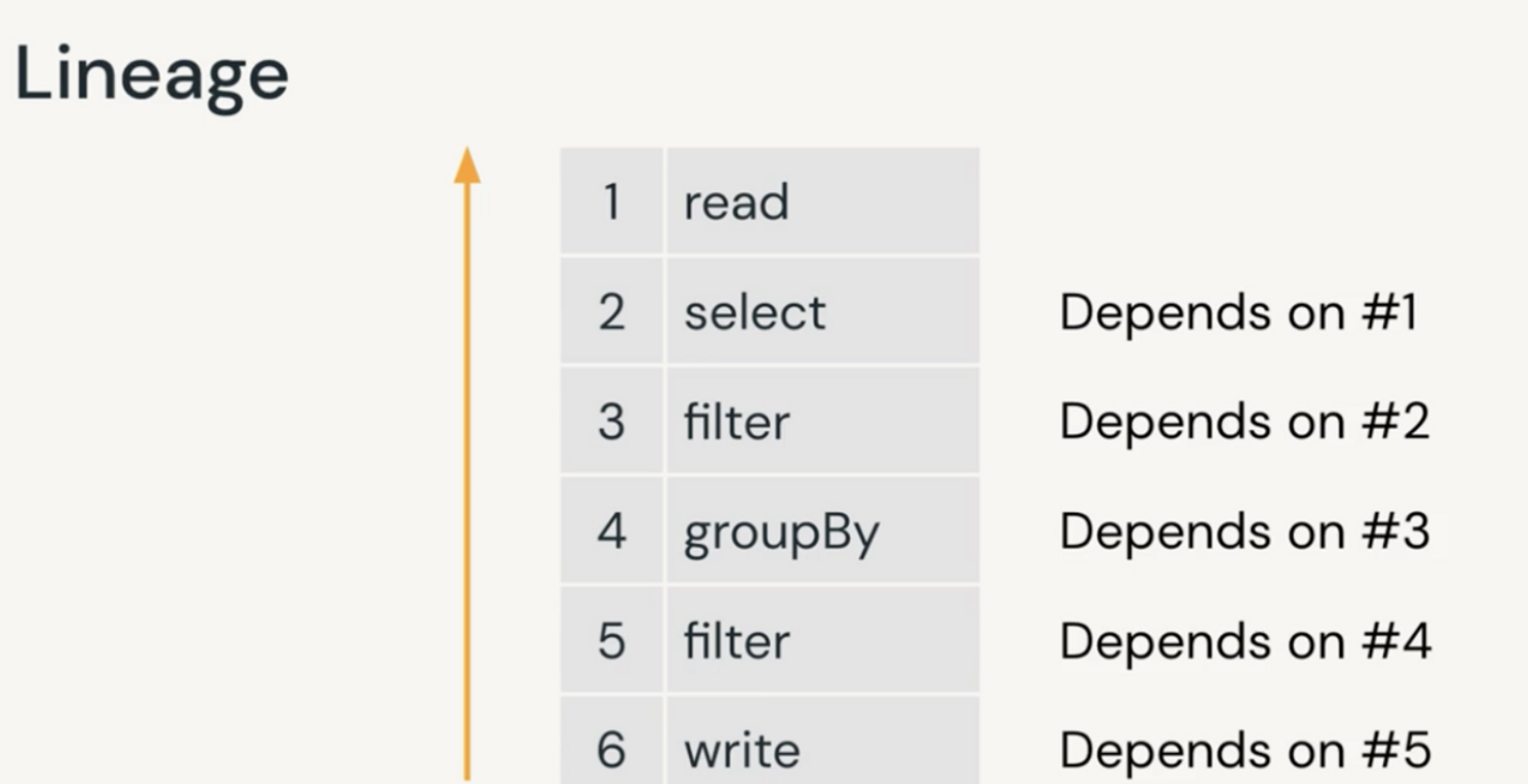

Another characteristic of Spark is lazy execution. When you specify transformations on a Spark DataFrame, Spark records lineage and only start the computation when an action is triggered (refer to my previous post about SparkSQL programming for more information on transformations and actions)

Under the hood, SparkSQL uses Spark Catalyst Optimizer to optimize query performation, similar to how a relational database or a data warehouse plans their query jobs.

Spark Catalyst Optimizer

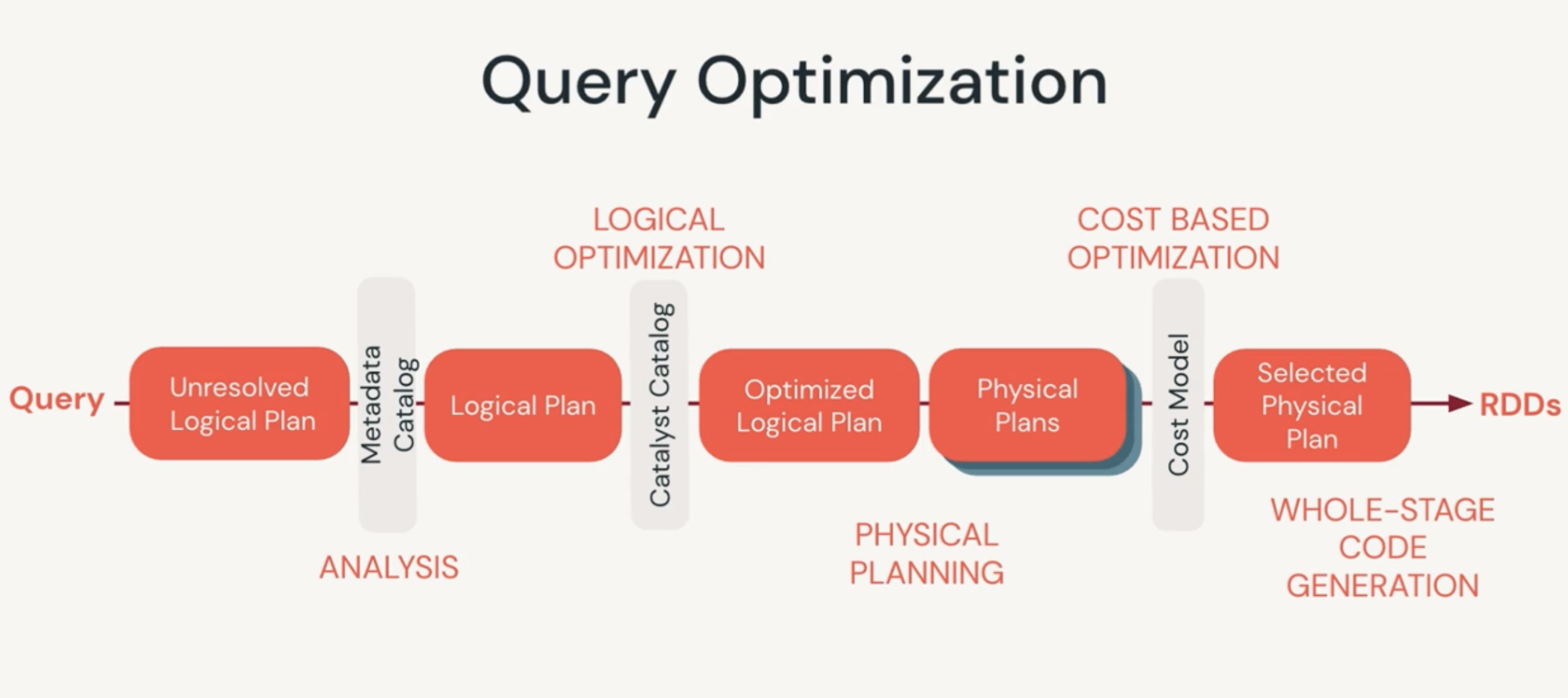

The Catalyst Optimizer is a component of Spark SQL that performs optimization on a query through 4 stages:

- analysis: create abstract syntax tree of a query

- logical optimization: create plan and cost-based optimizer and assign costs to plan

- physical planning: generate physical plan based on logical plan

- code generation: generate java bytecode to run on each machine, spark sql acts as a compiler. Project Tungsten engine generate RDD code

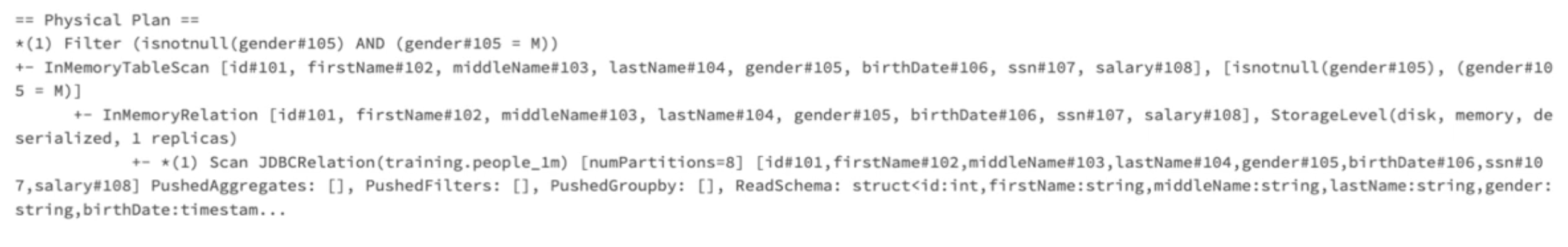

Catalyst Optimizer is a rule based engine that takes the Logical Plan and rewrites it as an optimized Physical Plan. The Physical Plan is developed BEFORE a query is executed

To view the Catalyst Optimizier in action, use df.explain(True) to view the Logical and Physical Execution plans of a query.

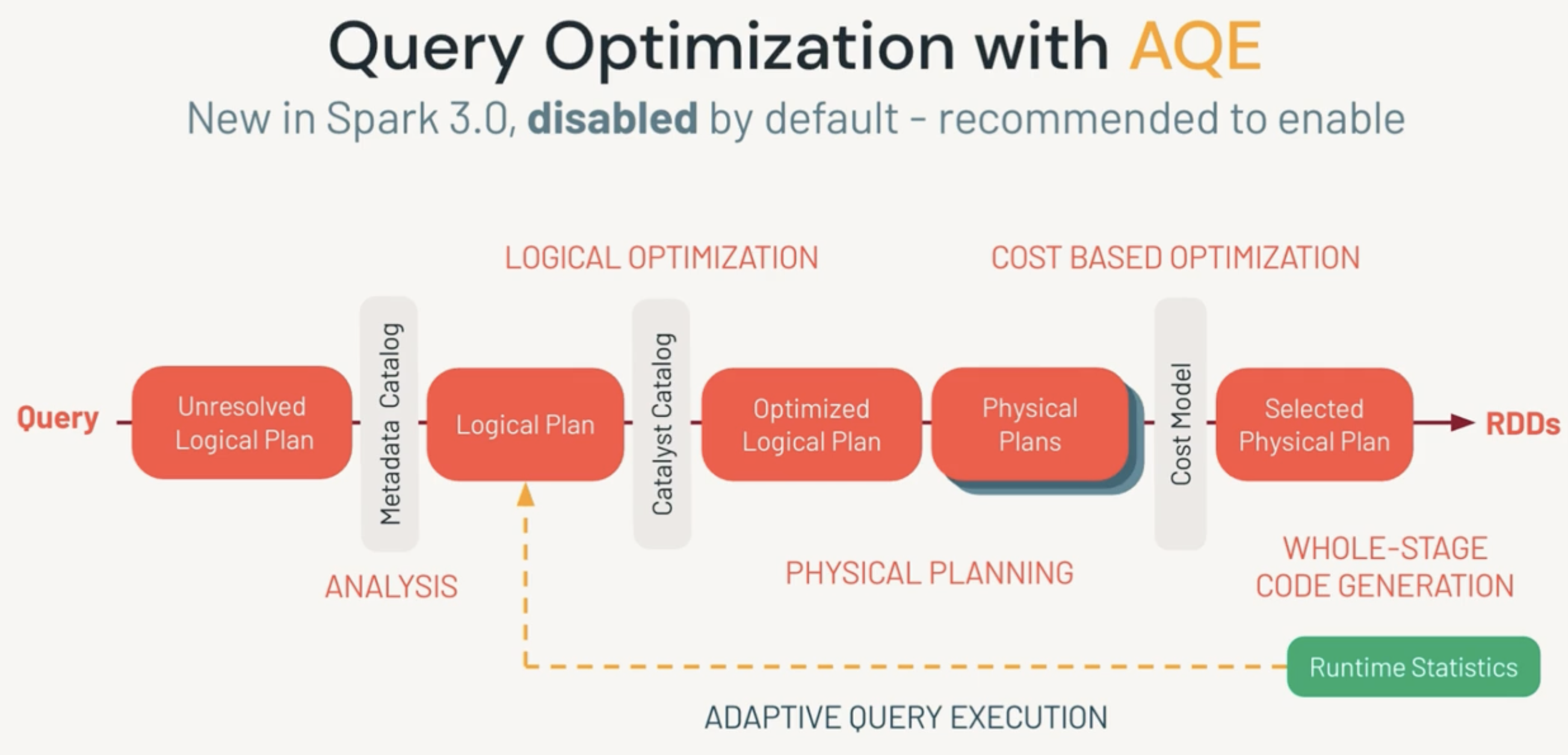

Adaptive Query Execution

In Spark 3.0, Adaptive Query Execution (AQE) was introduced. One difference between AQE and Catalyst Optimizer is that AQE modifies the Physical Plan based on Runtime Statistics, so AQE can tune your queries further on the flight. So you may think that AQE is complimentary to Catalyst Optimizer.

For example, during runtime, based on the new information that is previously not available during planning, AQE can decide to change your join strategy to Broadcast Hash Join from Sort Merge Join to reduce data shuffle. Or AQE can coalesce your partitions to optimal size during shuffling stage, or help improve Skew Join.

This option is not turned on by default in Spark, you can enable by setting spark config: spark.conf.set(spark.sql.adaptive.enabled, True) , and it’s recommended to turn this on. However, If you run Spark on later version of Databricks Runtime, AQE is enabled by default.

Shuffle, Partitioning and Caching in Spark

We established that Spark processes data in parallel by splitting up data into partitions and move (shuffle) them to each executors so that they can run a task on a small subset of data in memory.

Shufflings, partitionings, and memory can potentially dictate Spark performance. So if you understand these terms in depth, debugging Spark can become much easier, which I explained further in another post about Debugging Long Running Spark Job

To process your data, Spark will first have to ingest files from disk to memory, and by default it reads data into partitions of 128MB. If there’s any wide transformation on the DataFrame, Spark needs to repartition the data and move partititions to cores for processing. The implication of this is each partition will have to fit into the core’s memory or you will have spill or OOM errors. If partitions are not evenly distributed, you can have skew (which means some executors have more works than the others). Correctly tuning partitions upon ingestion and upon shuffling stage can help improve your Spark jobs.

Partitioning

There are 2 types of partitioning:

- Spark Partition: partition in flight (in RAM)

- Disk Partition (Hive partition): partition at rest (on disk)

When Spark read data from disk to memory (dataframe), the initial partition in the dataframe (in MEMORY) will be determined by number of cores (default level of parallelism), dataset size, spark.sql.files.maxPartitionBytes config, spark.sql.files.openCostInBytes (default 4MB, overhead of opening file). Remember that this is the size of the partition in Memory, irrelevant to what it is on disk.

Check number of partitions in DataFrame when ingested from disk to memory with df.rdd.getNumPartitions(). We can estimate the size of your dataframe in memory by multiply the number of partitions in memory by the partition size.

- By default, each partition has the size of 128MB but you can set with

spark.sql.files.maxPartitionBytes. A situation when setting this config can be beneficial is to write data to 1GB part files.

- Don’t allow partition size to increase >200MB per 8GB of core total memory, if more than that, increase number of partitions. It’s better to have many small partitions than too few large partitions.

- It’s best to tune the number of partitions so it is at least a multiple of number of cores in your cluster. This allows for better paralellism. Run

df.rdd.getNumPartitions()to check the number of partitions in memory. - In case if you want to change partition size at runtime, you can run

coalesce()andrepartition(). Coalesce can only reduce the number of partitions and increase partition size, but as a narrow transformation with no shuffling, coalsce is more efficient than repartition. Repartition returns new DF with exactly N partitions of even size. It can increase or decrease your partition count, but it requires expensive data shuffling

Shuffle

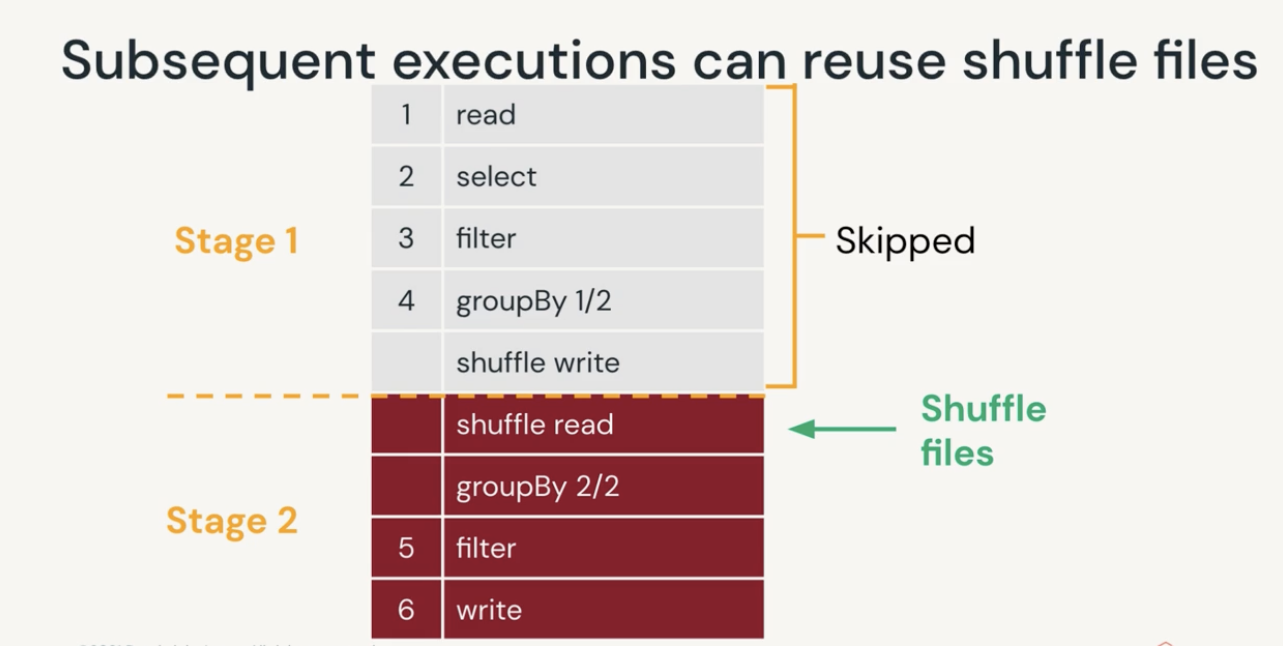

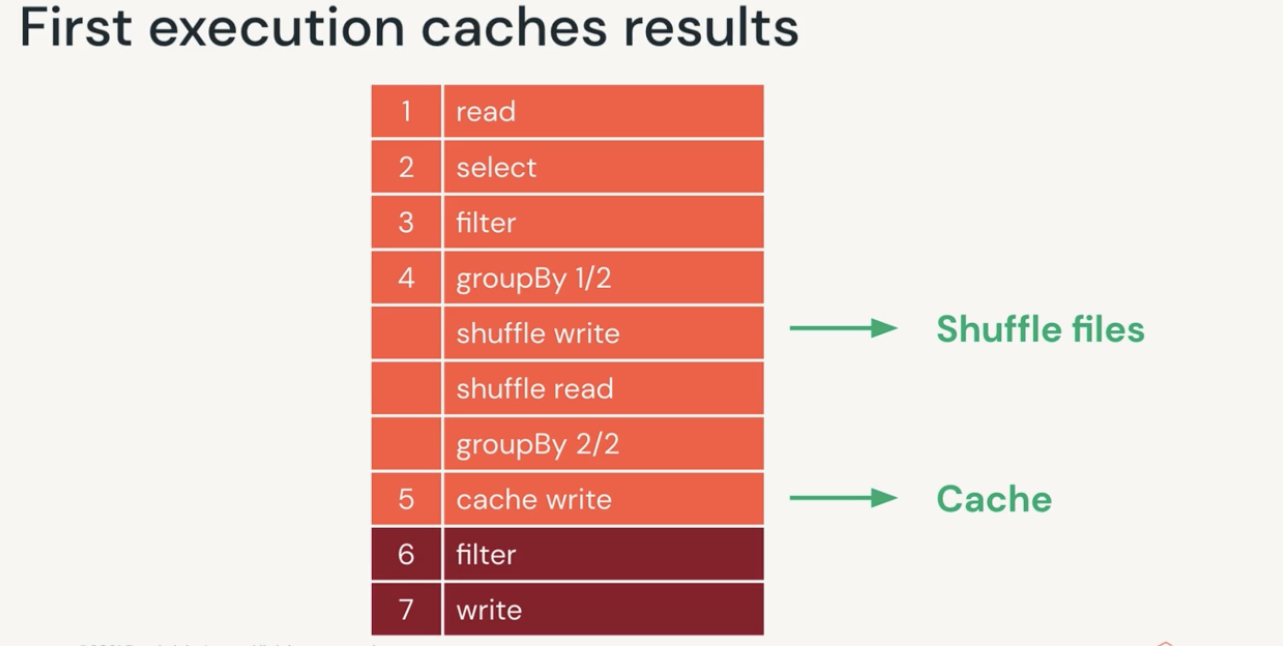

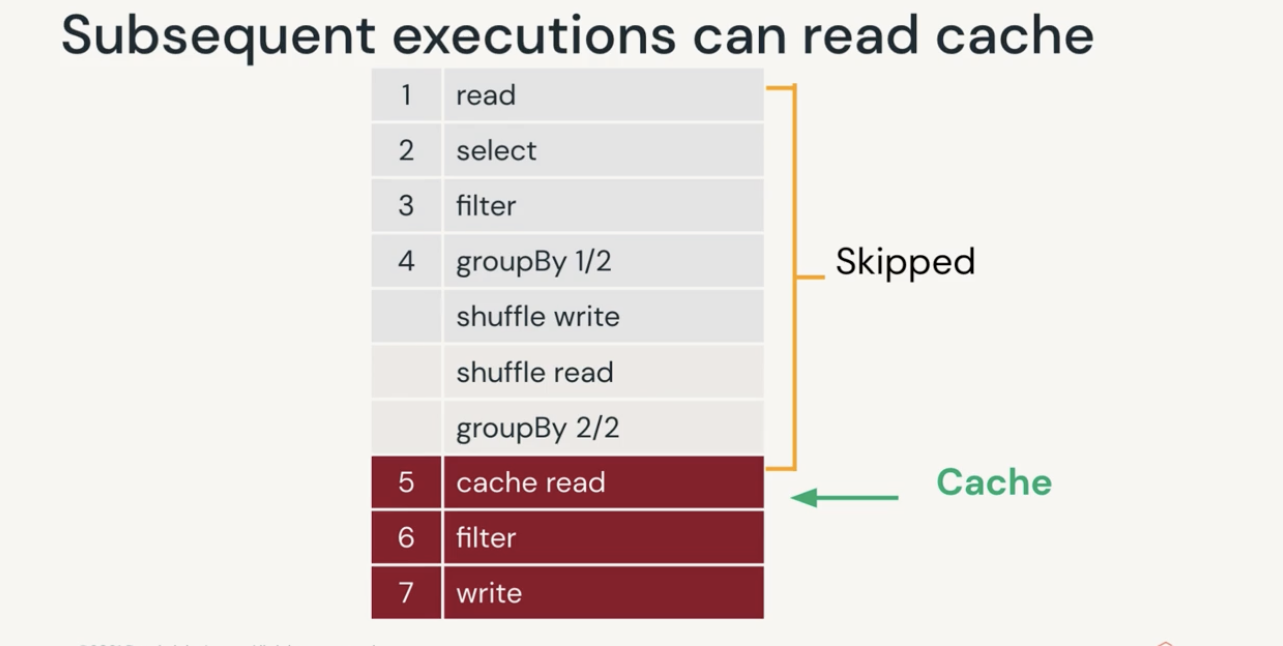

Shuffle is one of the most expensive operation in Spark. In every wide transformation (for example a groupBy), shuffle create multiple stages:

- First stage will create shuffle files (shuffle write)

- Subsequent stages will reuse those shuffle files (shuffle read)

- If cache is used, first stage can create shuffle files and cache the results, later stages can read from cache with improve the performance

The issues with shuffle partitions are:

- Too many partitions and you may have empty or very small partitions which put pressure on driver. This issue can be solved by enabling Adaptive Query Execution (AQE) as explained above

- Too few partitions and big partitions can cause spill or OOM. Correctly setting the

spark.sql.shuffle.partitionsbased on the rule in partition section can help. This setting indicates how many partitions Spark will create for the next stage, and it MUST be managed by user for every job.

Besides, there are a few techniques to mitigate excessive shuffles in my previous post Debugging Long Running Spark Job

Cache in Spark

By default, data in a DataFrame is only present in Spark cluster while bing processed during a query, it won’t be persisted on a cluster afterwards. However, you can explicitly request Spark to persist DataFrame on the cluster by invoking df.cache. Cache can store as many partitions of the dataframe as the cluster memory allows

Note that cache is another type of persist: df.cache is df.persist(StorageLevel.MEMORY_AND_DISK). This stores partitions in memory and spills excess to disk.

Cache should be used with care because caching consumes cluster resources that could otherwise be used for other executions, and it can prevent Spark from performing query optimization. You should only used cache in below situations:

- DataFrames frequently used during Exploratory Data Analysis, iterative machine learning training in a Spark session

- DataFrames accessed commonly for doing frequent transformations during ETL or building data pipelines

- Don’t use when data is too big to fit in memory, or only need infrequent transformation

When you use cache() or persist(), the DataFrame is not fully cached until you invoke an action that goes through every record (e.g., count()). If you use an action like take(1)w, only one partition will be cached because Catalyst realizes that you do not need to compute all the partitions just to retrieve one record.

Don’t forget to cleanup with df.unpersist to evict the dataframe from cache when you no longer need it.